We talked to local artists, Abraham Lara, Levi Morales, and Sebastian Lara about their upcoming show, Keep Dreaming, opening at Zeitgeist on August 6, 12-6pm. Together they make up Barbarian.

Question: How would you describe your work?

Abraham (Abe) Lara: I approach my paintings as a songwriter would a song.

I think it’s about being honest and about seeking truth at some capacity. Sometimes it’s found in beauty, and other times being reflective of the world. Curiosity and play are big factors to how I approach it.

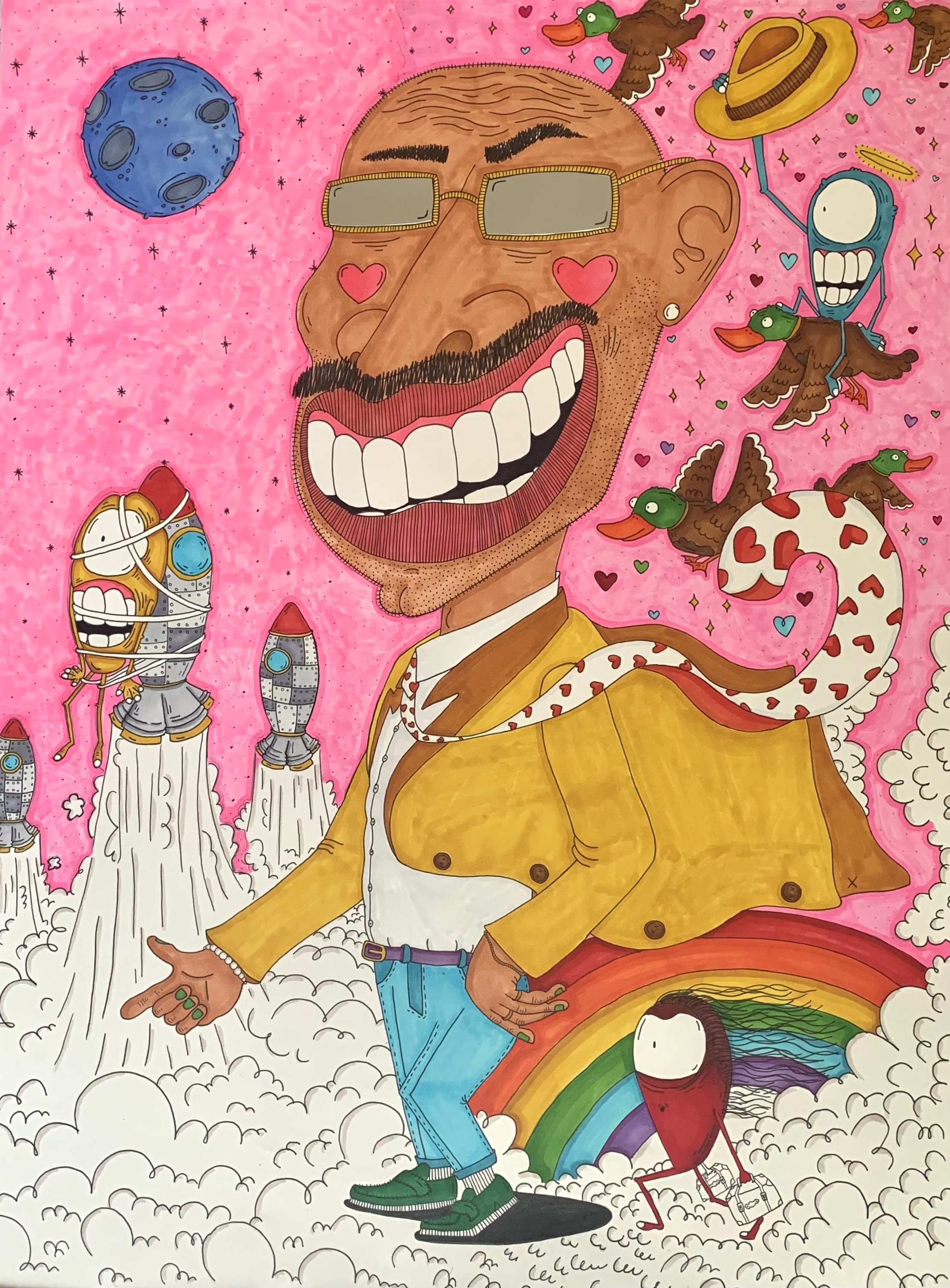

Abraham Lara, Too Much Information

Levi Morales: My work is the accumulation of my experiences on this world. Following what sparks my curiosity and also what makes my heart break, is what I currently enjoy doing. My work is about waste and switching the perspective of how waste is viewed. The things we discard so easily can become beautiful/fresh again with the right vision.

Sebastian Lara: I create as if it was a journal, with honest thoughts and colorful language. It’s usually a reflection of personal experiences and observations of what the world is going through at the moment.

Q: How does this time inform your work?

Abe: Up-cycling has become a big component of our creative process. Whether it be a canvas or a t-shirt, this is the time to use the discarded. Use what you have, and thrift stores are our best friends.

Levi: We live in a time of fast fashion and constant Amazon delivery. Barbarian upcycles materials to create new pieces. My work specifically uses Cardboard, scrap papers, and thrifted fabrics. I use materials that there is a lot of waste of. Most of which just end up in landfills that hurt our planet. Abe and I believe we can make art with what we already have.

Levi Morales, YOU TAKE MY BREATHE AWAY

Sebastian: Reusing and up-cycling have been implemented in my creations in order to prevent waste, I embrace and use what I have around me to make something greater.

Q: What themes are you currently exploring?

Abe: The theme of self has been pretty prominent. I find it as a true way to connect with the audience. When you’re able to tap into your personal experiences and share them, more often than not people find themselves in those experiences as well.

Levi: I’m currently exploring upcycling, waste and the push and pull of the canvas.

Sebastian: I’m addressing a lack of awareness and the disconnection from the world. My work is situated within the connecting threads of life and death. Each piece references elements of nature incorporating recognizable and exaggerated features that represent universal themes of environmental health, intentional acts of love, and our global fragility.

Q: How does being part of a collective impact the way you create, and

how did it come together?

Abe: It’s great when there are conversations and you can feel everyone is in sync and it’s the greatest feeling. It becomes difficult when you fall out of sync. Not seeing eye to eye can make it hard for a creative collective to work in harmony. As far as how we’ve met, we’ve been knowing each other way before we became artists. So there’s a history and things we have in common that made this whole thing come about.

Levi: I absolutely love working as a collective. Don't get me wrong, it's tough but there is nothing like a team in sync working towards one goal. Working together impacts my approach towards my work and gets me out of comfort zone. I see their process and it inspires me to fine tune my own. Being wrong or not always having a hand in the final piece teaches you to trust one another's abilities. It helps you grow. The team I have the pleasure of working with now are also childhood friends so communication is a little easier than most.

Sebastian: Anytime you have more than one great mind in a group, there are moments where it feels and sounds like a church choir but there are moments when it gets difficult and things don’t fall into place. But because we grew up together, we’ve learned to listen, and have conversations that build us up as one.

Q: Where do you see the line between art and craft, and where do you fit into that?

Abe: I actually had to google what craft was. Craft is supposedly something that is purely technical and about skill. Art is about trying to convey something, which I find the line between art and craft to really be subjective. All I know is that we learned about dada and pop art before we started making shirts and paintings. We’ve always had the question of why and what are we wanting to say with this with anything we’ve ever made. Shoutout to Guy!

Levi: I don't see a line. I just create. I spend time perfecting my craft so I can make art that more clearly conveys what I want to express.

Sebastian: Art always has something to say and craft is purely skill and technicality. You can always find a balance between the two. I find myself right on the line as a skilled and technical artist but still crave to say something with my work.

Sebastian Lara, Apocalypse

Q: What artists inspire you?

Abe: Sonnenzimmer, Kendrick Lamar, Levi Morales, The 1975, Sebastian Lara, Callen Schaub, Virgil Abloh, and always Duchamp.

Levi: I draw my inspiration from everywhere. Music, shows, nature, and community. All forms of art fuel my creation process. I pull inspiration from the greats and in the artworld and the movements that they help start. Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Picasso, Basquiat, and a lot more. My friends and local artist Abraham Lara and Sebastian Lara are also a source of inspiration. It all inspires me.

Sebastian: I pull a lot from Jean Dubuffet, Levi Morales, Tyler the creator, Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, Abraham Lara, and Prince.

Q: What do you like about being an artist in Nashville?

Abe: We’ve been here our whole lives, so it helps knowing fellow artists and having connections.

Levi: I enjoy the diversity. The different perspectives from unique individuals. I also like the energy of a growing city. Even though traffic sucks.

Sebastian: I’ve lived here all my life, so I’ve seen Nashville grow immensely, meeting new creatives and making new connections is what makes living in Nashville worthwhile.

Q: What do you wish would change about the arts in Nashville?

Abe: I wish there was a place where artists could rent for a studio space to have more of a community going. Having gone to Watkins College of Art it was nice to having been constantly surrounded by artists and seeing what everyone was working on. I would make a place where artists could work from and also have a gallery of sorts.

Levi: I would like to see more opportunities given to the minority population in Nashville. In Antioch, Murfreesboro, and Laverne there is a rich diversity of artists. I would like to see more promotion in those areas to pull in local artists. There isn’t spot for artists to come together. Having a sorta home base would allow us to get more connected and organized.

Sebastian: More artists coming together.

Q: Where would be your dream to see your work one day?

Abe: It would be nice to show at the Frist someday - that would be cool.

Levi: It would have to be seeing my work being appropriated and inspiring new kinds of work by others . As far as what space I dream to see my work in, I would love to see my work on the walls of someone’s house.

Sebastian: Showing at the Julia Martin Gallery would be absolute craziness.